4 Flower Threats That Could Cost You Your Crop

THE MOST COMMON ISSUES OUTDOOR GROWERS FACE AS HARVEST APPROACHES—AND HOW TO PLAN AHEAD

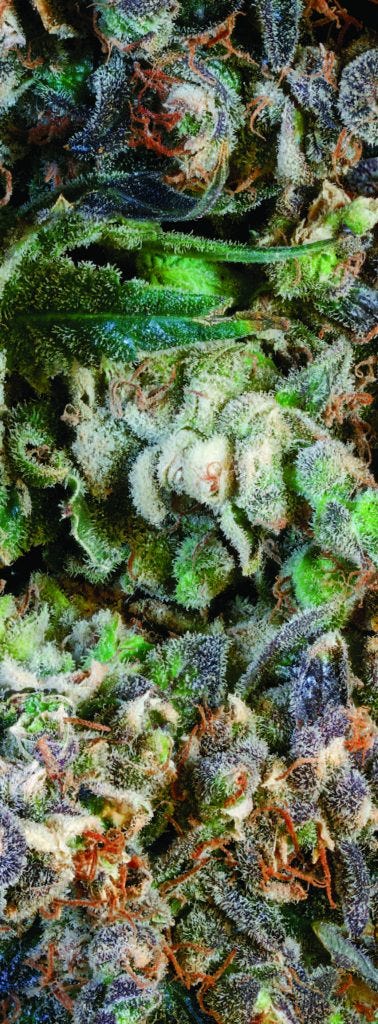

During flower, outdoor cannabis growers face one of the toughest parts of any crop production season.

Inflorescence, or the process of flowering, is a point in a plant’s life cycle where they are in their most delicate state.

During cannabis flowering the options for controlling unforeseen environmental pressures are extremely limited, meaning the results of any choice in these moments are at their least forgiving. This is especially true for those using an organic approach.

Knowing the most common flowering phase pests and having a proper IPM strategy in place long before plants begin their pre-stretch is half the battle.

The usual suspects to be wary of during flowering are:

- Russet Mites

- Powdery Mildew

- Moth Larvae (caterpillars or worms)

- Botrytis

Flowering (Bloom) Phase In the United States, most photoperiod cannabis plants usually start their transition to flower in late July to August, when days begin to shorten.

Outside of a few “Goldie Locks” zones around the country, most flowering windows come to a close between October (Croptober) or November without using a season extender of some kind. In most cases, the open-air growing window will close abruptly, so picking a proper variety for a specific environment and its unique challenges is the first step of protecting your hard work from flowering time pests. Why fight the pests during flower if you can get a plant to the finish line before the worst characters rear their heads?

Once the varieties are selected, it’s time to identify the biggest characters that growers will have to protect a cannabis crop against.

These pests were selected because their populations tend to increase as the environment transitions and creates the right conditions not only for flowering cannabis, but also for rapid pest growth.

Note: Before going forward remember, the “I” in IPM means integrated, and every method discussed below is not meant as a replacement for plant-conscious cultural practices like proper daily scouting, thinning, pruning, lollipopping, training, or trellising.

These practices should be all done in conjunction with one another. Prepping a healthy environment with proper airflow will save a grower money, labor, and headaches.

THREAT 1: The hemp russet mite (aculops cannabicola) is an almost microscopic mite, just bigger than the width of a human hair.

In 2016, growers were faced with The Great Russet Mite Panic, and many who lost crops were forced to implement production-wide IPM programs.

Russet mites belong to the Eriophyidae family, which is home to rust and gull mites. Russet mites were relatively unknown in cannabis until individual states started enacting cannabis legalization in 2015, opening up large-scale cannabis clone trading regionally and globally.

This free exchange led to The Great Russet Mite Panic in 2016, where growers were losing crops and cannabis growers had to begin actual production crop IPM programs.

For outdoor IPM purposes, Hemp Russet mites are considered a flowering pest because of how their life cycle works in nature.

The hotter and drier it is, the faster Hemp Russet mites cycle through their developmental instar (molting) phases. Late summer, just as cannabis begins to flower, is when these environmental variables line up for a Russet mite explosion.

Hemp Russet mites can go from egg to a breeding adult individual in as fast as 8-14 days if it is 77ºF or higher. Once they reach adulthood, their lifespan is roughly three weeks. A female in those three adult breeding weeks can lay approximately 12-24 eggs each.

This life cycle speed increase taking place in late summer means that as pre-stretch starts, novice growers won’t notice damage until the plant is done stretching and the bud sets begin to grow in deformed or stunted. By then it’s too late.

To combat environmental timing, Russet IPM strategy must be preventative.

Sulfur and insecticidal soap are the primary pesticides used during vegetative growth (including through the pre-flower stretch phase).

This organic IPM approach to Hemp Russet mites starts with wettable, micronized sulfur, an element trusted to control pests since ancient Egypt.

The primary benefit of using sulfur through pre-flower is that residual sulfur on the vegetative leaves will keep russets from establishing for at least two additional weeks, long enough for the temperatures to drop to a point where russet mites can’t come back and thrive.

Stopping the use of sulfur during pre-flower is important because using it after buds have begun to form will make everything taste or smell like sulfur.

Once pre-flower is done, releasing Amblysieus Andersoni predatory mites (known to feed on Russets) will help take your cannabis plant to the finish line.

Photos from the top.

- By Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.1

- Cloyd, R. (2020, July). Win the Fight Against Hemp Russet Mites. Cannabis Business Times. https://www.cannabisbusinesstimes.com/article/ win-the-fight-against-hemp-russet-mites-cannabis-pest-control/

THREAT 2: Powdery Mildew is another seasonal threat to crops during this shift to flower.

Unlike other mildews, Powdery Mildew doesn’t need water to sprout spores. It just needs a relatively humid environment, which means the hot days and cold nights of late summer when cannabis transitions to flower are perfect—these temperature swings create a humid environment that’s perfect for mildew.

The production rate of candida—the fuzzy white fruiting spores of powdery mildew—is strongest at 77ºF, and ceases to produce spores at temperatures above 86ºF.

Contrary to popular belief, Powdery Mildew is not systemic.

It is an obligate biotroph, which uses cells called haustoria to get through the epidermal layer on a plant to extract nutrients for its own growth. However, the ability to penetrate the epidermal layer with these cells does not equal a systemic infection.

Powdery Mildew reproductive candida do not travel through the xylem to create fruiting bodies elsewhere on the plant, which is needed to cross the systemic threshold.

Some of the most common strains of Powdery Mildew to infect cannabis are Golovinomyces spadiceus, Golovinomyces ambrosiae, and Podosphaera macularis.

The silver lining with Powdery Mildew is that it is easy to control if you have a preventative IPM strategy in place before flowering starts.

Even better is that the same micronized sulfur treatment for Russet mites will also be effective against Powdery Mildew.

The same way sulfur residual works for Russet mites also applies to Powdery Mildew and its spores (once the pre-flower stretch has stopped).

The only difference is the mode of action in which it kills the pest: with Russet mites, the sulfur disrupts the chitin synthesization in exoskeleton cells, causing death. With Powdery Mildew, sulfur works by disrupting fungal cell respiration, causing death.

Sulfur's ability to disrupt multiple different pests' life cycles means you can scale back on having a lot of different pesticides on hand for individual pests, which cuts down on application labor and pesticide costs.

3. Mirza, M. (2018, February 22). Beware of Powdery Mildew - Grow Opportunity. Grow Opportunity Magazine. https://www.growopportunity.ca/ beware-of-powdery-mildew-32281/

THREAT 3 & 4: Budworms and Botrytis are the two flowering-time pests that break more hearts than any other pest a grower will encounter during cannabis flowering.

The dramatic reveal usually happens at harvest time: as a branch is chopped off to be big leafed (removal of fan leaves) and as the petiole is being pulled away, the bud attached to it simply disintegrates because the center of it has been liquefied by pests.

All the hard work, a ll the toiling, was for not. In a situation like this, the culprits are almost always Budworms and Botrytis, the final hurdles a flowering cannabis plant will face before harvesting. Caterpillars, or “Budworms,” are the larvae of moths which hatch from eggs laid by a female moth.

The purpose of laying these eggs on plants is to have a readily available food source for the larvae to get through tough environmental conditions.

Although the physical damage done by the caterpillar is not visually alarming, don’t be fooled; their voracious appetite means budworms constantly excrete a more insidious pest that will make a growers heart drop.

Botrytis Cinerea, or gray mold, is a systemic, necrotrophic fungus, killing its host to gain its own nutrition.

Although it is systemic, it also spreads through sporulation. Botrytis is the fungus that is responsible for “bud rot” in cannabis. As with previously discussed pests, environmental conditions play a huge factor in Botrytis finding a foothold.

Caterpillars and Botrytis are discussed together because they’re uniquely connected: Caterpillar larvae carry botrytis candida on their protective cuticle as well as in their gut. So an IPM regiment should reflect this relationship as well.

In this way, controlling caterpillars is also a form of Botrytis prevention.

I recommend a biweekly rotating defense of Trichogramma Wasp releases and Bacillus Thuringiensis (BT) pesticide sprays starting in late July or early August.

Alternate treatments weekly between these control methods through mid-October.

Unlike Powdery Mildew that forms on the outside of the plant, sulfur residue won’t help control potential Botrytis growing in the center of a cola because, if used properly, the residue remains only on vegetative growth, where it dried after being sprayed in pre-flower.

Trichogramma wasps work by infesting moth eggs with their own eggs; the moth eggs act as a readily available food source for moth larvae after hatching.

These wasp eggs take about five days to hatch, which is why biweekly releases help to build up breeding populations. If this is done for 3-5 years it is possible to establish a natural breeding population in a field.

BT is a natural microbial byproduct of the fermentation process, that is ubiquitous in nature and is not lethal to humans, but harmful to caterpillars feeding on your plants.

When caterpillars ingest BT or BT toxins, it triggers a crystallization reaction in the guts of caterpillars which cuts up their insides, causing them to starve, effectively liquifying budworms from the inside. BT and BT toxins are active on plants in normal growing conditions for 3-7 days after application.

Lastly, although Budworms account for a large percentage of Botrytis infections, they are not the only way a cannabis plant can contract it.

Botrytis is always in the air, waiting for the environment to be just right to find its host.

Unlike Powdery Mildew, Botrytis needs water to be present in the plant from sources like rain, irrigation, or condensation to sprout.

Stagnant water hanging around is the enemy. Waterlogged soils due to poor drainage, along with high humidity, will slow transpiration down and hamper a plant’s ability to naturally move water away from itself. Add in poor air circulation and a plant has been primed for a guaranteed Botrytis outbreak.

Three of the common Budworms found on cannabis plants are:

- Heliothis armigera

- Heliothis viriplaca

- Chloridea virescens

Subscribe to our Substack to receive new content automatically

This article is featured in Vol. 5 of The ETHOS Magazine.

Grab a collector's edition of the ETHOS magazine in print HERE.